What’s the market for Ion Markets?

With whispers swirling that Ion’s chief executive is looking to cash out on his tech conglomerate, big changes could be coming to the world of fixed-income software.

It’s been a tough year so far for Ion Markets, the aggressively acquisitive division of Ion Investment Group that has snapped up names like Fidessa and Dash Financial. Now, there are whispers the capital markets tech conglomerate has been exploring the possibility of a sale.

Those claims come from various quarters, but not from anyone who would have direct knowledge. Still, indulge them for a moment: the company has been able to rapidly achieve a dominant position in many of its businesses, so what kind of exit might be open to it? Who would have the capital, and the stomach, to buy it?

WatersTechnology spoke with more than a dozen industry participants for this article, eight of whom repeated the rumor that Ion Markets, the largest and most expensive-to-operate jewel in Ion Group’s crown, was looking for one or more buyers.

A spokesperson for Ion declined to comment on the acquisition rumors.

Only a handful of vendors could afford to buy Ion Markets outright, says Virginie O’Shea, founder and CEO of Firebrand Research. The firm has acquired dozens of assets over the years, and some of them, such as equities darling Fidessa, sit outside the business Ion has traditionally been known for—fixed-income software—making it difficult to pinpoint an obvious buyer.

“Any acquirer would have to think long and hard about which solutions and services are worth investing in and which should eventually be sunsetted, which would likely mean more concentration in the market,” O’Shea says. “Acquisitions always increase concentration, and regulators may step in if there’s too much perceived concentration risk to block the sale.”

A buyer taking Ion Markets in its entirety would need to be a mega-vendor or market infrastructure provider with a hefty market cap, which would make any list of candidates relatively short, O’Shea says.

Several sources speculated on who might throw their hat in the ring, often pointing at the operators of the three leading fixed-income trading platforms—Bloomberg, MarketAxess, and Tradeweb. In an unusual move, the trio of competitors banded together recently on a bid to potentially transform fixed income in a different way: the construction and operation of a consolidated tape for the European bond market.

Despite the new alliance, the three are fierce rivals in the world of fixed-income technology. Ion, as an asset, would put any of one of them well ahead of the other two, says a former employee of Refinitiv, which itself competes with Bloomberg in the data and trading terminal business but has partnerships with Tradeweb and MarketAxess. “[It] makes you wonder about the regulatory implications,” they say.

Representatives for Bloomberg, MarketAxess, and Tradeweb each declined to comment.

An industry consultant believes Bloomberg would be the single most likely candidate as a buyer for all or parts of Ion. If the data giant did step forward, it could re-unite the severed Broadway Technology, which was split up by the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority in 2020 after a complicated deal between Broadway and Ion failed to clear regulatory hurdles. After a months-long probe into Ion’s attempted acquisition, the competition watchdog ruled that Ion could keep the vendor’s foreign exchange business, including order management system Barracuda, but had to spin off the fixed-income franchise, which Bloomberg snapped up.

“I think Ion would complement [Bloomberg’s] Broadway purchase and bring 40-odd new clients in,” the consultant says.

However, others familiar with the Ion M&A talk said, due to monopolistic concerns, a Bloomberg-Ion tie-up would be a non-starter for regulators.

In January, a ransomware attack by the hacker outfit LockBit struck Ion Markets and 42 of its bank clients, drawing outrage from clients and the gaze of international regulators to the secretive company and its reclusive founder and chief executive, Andrea Pignataro.

The consultant says a potential buyer of Ion Markets would need to have “deep pockets” to cover any future legal action arising from the hack.

In theory, the pockets of Bloomberg, Tradeweb, and MarketAxess could all be deep enough to buy Ion Markets—or parts of it. Bloomberg, a private company, is valued at more than $50 billion, as of 2021 estimates. Tradeweb claims a market cap north of $14 billion, and MarketAxess sits at nearly $9.5 billion.

Ion is harder to value. Backed by private-equity firm Carlyle Group, the company publicly discloses very little about its financials, and estimates by public aggregators such as ZoomInfo, Crunchbase, and DealRoom give wildly varying numbers.

The clearest insights that can be found on Ion’s financials come from a February 2023 interview given by Pignataro to Italian newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore, in which the executive said that Ion’s cash flow is €1.8 billion ($2 billion), and the company is five times levered.

“I can see why all of them would want to buy Ion; I could see why none of them would want to buy Ion,” says the former Refinitiv employee. “You can’t say that none of them make sense, and you can’t say that any one of them are head-and-shoulders above the other. These companies are big rivals in the fixed-income space. Ion would put one of these guys ahead of everyone.”

Recent high-profile deals in the fixed-income space have signaled an appetite for growth. The combination of more venues, greater competition, deeper liquidity, and electronically tradeable assets is fostering consolidation among vendors. In addition to Bloomberg’s purchase of Broadway, Trading Technologies, a futures trading software provider, bought fixed-income trading platform AxeTrading; both moves satisfied the buyers’ desires to expand their trading capabilities and meet customer demand for access to wider, multi-asset trading.

The trend toward consolidation is evident beyond fixed income. Data vendors and exchanges have been eager to acquire and merge as they also look to expand their product and services and compete with Big Tech players—and they’re willing to pay big. In a blockbuster deal from June, Nasdaq forked out over $10.5 billion for Adenza, the combined entity comprising legacy vendors AxiomSL and Calypso Technology and a provider of risk management and regulatory software. It marked Nasdaq’s biggest acquisition to date.

“If you look at the Nasdaq deal with Adenza, it makes a lot of sense to buy an incumbent that needs modernization, rather than build something to disrupt,” says the CEO of a large financial technology company.

Two other sources believe it would make the most sense for Ion to break up its Markets division—and perhaps its other silos, which include Analytics, Corporates, Core Banking, and Credit Information—and sell the various parts to multiple buyers. “It’s hard to see anybody wrapping their head around the whole package,” says a former head of e-trading at a US bank.

The former Refinitiv employee compares Ion’s business strategy to that of SunGard, where CEO Cris Conde bought “a whole bunch of businesses” and then put one brand on them and sold their services with one sales force. “They didn’t even pretend to integrate the businesses together from a product perspective. Depending on the circumstances, that’s not an altogether bad way of doing things. It’s running it as a portfolio of investments as opposed to an integrated company.” (The source adds that they think LSEG is doing a good job of integrating the Refinitiv estate.)

This highlights, though, the complexity that would underpin any kind of deal—many of Ion’s acquired pieces have never been truly integrated. So a potential buyer—if they care about integration—would have to undertake “an unprecedented integration project” to get the systems to talk not only to one another, but to the acquiring firm’s tech stack, says the managing director at a competing trading platform provider. “I can’t imagine Bloomberg wanting to do that. Tradeweb just acquired Australian company [Yieldbroker]. MarketAxess I can see making sense, but only if we are talking about specific pieces.”

Other sources have noted the company that acquired SunGard, FIS, is rumored to be interested, as is Fiserv. Still others said a possible buyer could be a consortium of banks.

What does a new Ion mean for clients?

Any potential sale would lead to big changes for participants of fixed-income trading, who have dealt with years of sticky, long-term contracts with Ion, the market’s biggest vendor. When Ion entered the equities space with its acquisition of leading order management system Fidessa, some clients who had known of Ion’s reputation, but hadn’t used the vendor directly, voiced concerns about lowered service qualities and long, nearly inescapable contracts.

“A decent, well-funded owner might stabilize things,” says a second consultant. “And if there was some softening of the client contracts, this would be good for the market.”

In response to Ion’s rapid growth through acquisitions, in 2019, a group of European banks formed a consortium, dubbed Cohesion, in a move that was meant to allow its members to reduce their reliance on Ion. Though it appears the “Ion replacement” project never got off the ground, sources at the time expressed concerns around competition, sticky contracts, and high service costs, all of which contributed to the project’s formation.

The former head of e-trading says Ion’s acquisition and business strategy has never been clear to them.

“If you laid out a grid with products down one side and functionality—trading, back office, etcetera—on the other, I’d ask, ‘What’s your strategy here? Are you trying to fill the whole page? Have you got to have business in every one of these squares? Or are you trying to go down a vertical or horizontal first? Because I can’t see any logic to what you’re doing.’ It did feel that they were going for the whole checkerboard,” they say. “But to what end? I don’t know.”

The CEO of a trading infrastructure provider says a deal could be a double-edged sword for end-users: A new buyer could breathe new life into products that may have been underinvested in; but consolidation usually leads to price increases. “It’s the old ‘be careful of what you wish for’ thing.”

Given Ion’s huge portfolio of moving parts, sources say it would be a big asset to a potential buyer. And the fact that Ion isn’t always known for undergoing deep integrations or assimilations with its acquired companies could be a selling point—especially in fixed income, where market fragmentation makes the need for specialization greater than in equities and foreign exchange, the former Refinitiv employee says.

But Ion’s “grab bag” structure may not suit all acquirers, especially as system and app interoperability feature so high on users’ lists of wants and needs. A stormy relationship with some clients and a sizeable debt load might also be a deterrent for buyers.

“If you’re acquiring this company, you have to wonder if all the juice has been squeezed out of this orange,” the ex-Refinitiv employee says. “Can you extract any more value from it? And if these different products have been underinvested in, are you going to have to spend a lot more money to get them up to your standards, modernize it and get it back to state-of-the-art?”

Further reading

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@waterstechnology.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.waterstechnology.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

More on Trading Tech

For MarketAxess, portfolio trading buoys flat revenue in Q3

The vendor is betting on new platforms like X-Pro and Adaptive Auto-X, which helped forge a record quarter for platform usage.

Quants look to language models to predict market impact

Oxford-Man Institute says LLM-type engine that ‘reads’ order-book messages could help improve execution

JP Morgan pulls plug on deep learning model for FX algos

The bank has turned to less complex models that are easier to explain to clients.

Nasdaq says SaaS business now makes up 37% of revenues

The exchange operator’s Q3 earnings bring the Adenza and Verafin acquisitions center stage.

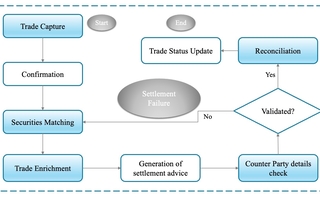

Harnessing generative AI to address security settlement challenges

A new paper from IBM researchers explores settlement challenges and looks at how generative AI can, among other things, identify the underlying cause of an issue and rectify the errors.

The causal AI wave could be the next to hit

As LLMs and generative AI grab headlines, another AI subset is gaining ground—and it might solve what generative AI can’t.

Waters Wrap: Operational efficiency and managed services—a stronger connection

As cloud, AI, open-source, APIs and other technologies evolve, Anthony says the choice to buy or build is rapidly evolving for chief operating officers, too.

BlackRock forecasts return to fixed income amid efforts to electronify market

The world's largest asset manager expects bond markets to make headway once rates settle.