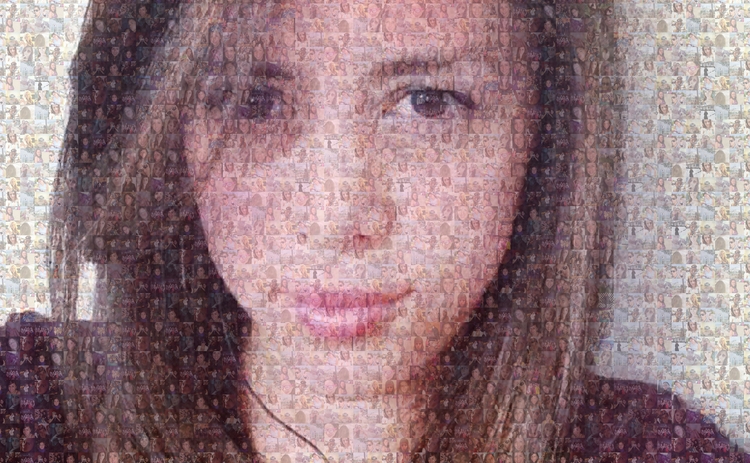

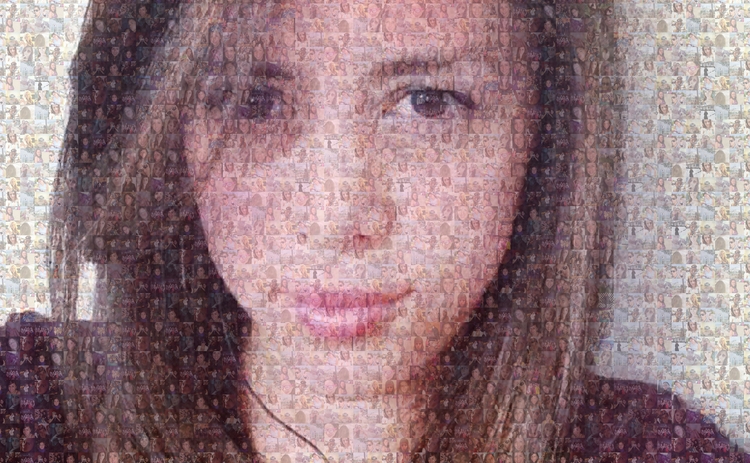

In Absentia: Remembering Sandra Villena and finding her killer

Sandra Villena, a 32-year-old market data professional on the rise, was murdered while on vacation in October 2022. Nearly a year later, her friends and family are still seeking justice, while they learn how to live with the absence that now fills their lives.

Need to know

Leer esto en Español, haga clic aquí.

It was the spring of 2020, and the world as they knew it was a couple weeks shy of ending. Americans nervously checked the news, watching as the novel coronavirus turned much of mainland China into a ghost town, and quietly hoped the chaos unfolding across the Pacific would not reach the same fever pitch on the Eastern side.

In New York, Sandra Villena, and close friend Farah Ali, arrived—running slightly late, in typical fashion—to The Farm Soho, a building of in-betweens and contradictions. Half co-working space and half party venue, The Farm offered four stories of charm, achieved through a synthesis of metal industrial details and rustic woodgrain. It was the first of March, and one of its lofts would host a small, intimate wedding, to be attended by a couple dozen friends and family and one dog. It would be a celebration of everything to come for the newlyweds and their guests, and it would also be, unwittingly, a final goodbye for some.

At the floor’s entrance was a table, on top of which sat a scattered pile of small wooden chips, each cut into the shape of a heart. The friends signed their names onto the blank pieces, then deposited them into a glass frame, painted white and gold—a substitute for a guestbook and an emblem of the couple’s formerly long-distance relationship that had spanned New Jersey to California. “Our adventure begins,” the frame read near the chip slot.

With the threat of a new and potentially deadly virus looming over the day like the sun, the wedding had been planned in a handful of weeks, and the day was no less stressful for the bride, Julia, than the weeks preceding it. The sight of her friends who had gathered on short notice brought her some ease.

Sandra, then on the cusp of turning 30, had arrived at the shindig wearing a blue and white sequined gown. She came prepared to dance, and she came with a speech.

Julia and Sandra had met through their alma mater, Baruch, a selective public college that’s part of the City University of New York system. In 2015, Julia was heading the risk management committee within the school’s Finance and Economics Society at the time Sandra joined the group. Julia would introduce Sandra in 2019 to Farah, who was involved in finance and STEM programs at Fordham University.

For most of the other guests, Julia’s wedding day was their first and only interaction with Sandra, a tender person who worked hard and played just as hard. But when tragic news of her untimely death would break two years later, those strangers remembered her from her speech.

Due to a videography mishap, no video or audio record of Sandra’s wedding speech exists. But through tears of joy, and perhaps some feeling of bittersweet, Sandra told the room that she was so happy for her dear friend, and that she hoped she would find a love like Julia’s to call her own someday.

Glasses clinked together in a chorus of agreement.

***

Fewer than three years later, Sandra’s life, and prospect of a happy ending, was cut short at the suspected hands of her boyfriend, Vicente Rosales, who remains at large. The pair had been vacationing in an Ecuadorian beach resort during October of last year, following Sandra’s completion of a lengthy and intense work project for market data consultancy CJC.

As it became clear that a new virus would profoundly alter life as we knew it, Sandra, a native of Peru and a naturalized American citizen, made the snap decision to move back to her hometown of Piura and be with her family only days after Julia’s wedding. It was there that she met Rosales.

A State Department official confirmed the death of a US citizen in Ecuador occurred in October 2022 and said the organization is “closely monitoring local authorities’ investigations.”

Shortly after her murder, Sandra’s family enlisted the services of a local attorney, Paola Floreano, to help find and bring Rosales to justice. But progress—if any was made—was slow, and Floreano did not show up to three scheduled interviews with WatersTechnology. So this summer, nearly a year after Sandra’s death, the family made the decision to start over from scratch, enlisting the help of Santiago Escobar, a founding partner at Escobar Associated Lawyers.

When he received the case, it was classed as a homicide rather than a femicide, which is a crime defined by the killing of a woman based on her gender. According to the Danish Development Research Network, a woman in Ecuador is killed on the basis of her gender every 28 hours, and it wasn’t until 2014 that the country criminalized this type of murder.

Broadly, femicides are characterized by at least one of four attributes set by the United Nations: stereotyped gender roles, discrimination toward women and girls, unequal power relations between women and men, or harmful social norms. Like other hate crimes, the burden of proof in a femicide case is higher than in a homicide case.

The task for Escobar is to prove, under Ecuadorian law, that Sandra’s relationship with her accused killer suffered from a power imbalance that ultimately and directly led to her killing.

“I’m saddened that it has taken this long to get to where we are now,” Escobar tells WatersTechnology through a translator, Sandra’s paternal cousin Rosa Loza. “Because if everything that is happening right now would have happened before, maybe he would have been caught by now.”

Knowing that Rosales could be anywhere in the world, the new legal team had a week-long deadline to rebuild the case. Escobar began seeking a Red Notice from Interpol, which requests that law enforcement worldwide help in efforts to locate and provisionally arrest a wanted person. After he worked with Ecuador’s attorney general to make the case for submitting a Red Notice request to the France-based Interpol—Escobar had to build a strong enough case that Rosales had fled the country and is still abroad—he received the approval for a Red Notice to be issued by the international police organization in mid-August.

Beyond the world-wide search for him, if Rosales is arrested, there comes the extradition proceedings, a six-month process on average. After that, he will stand before a tribunal of three judges, who will decide his guilt or innocence. Escobar and Sandra’s family are seeking a sentence of 34 years and six months—one year more than the age Sandra should have been this year.

Dorchen Leidholdt is an activist and leader in the movement to end violence against women around the world. Since 1994, she has served as the director of the Center for Battered Women’s Legal Services at the Sanctuary for Families in New York City, and she is the founder of the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, an international NGO opposing human trafficking and sexual exploitation of women and girls.

When an American citizen is killed abroad, the role that authorities play is, in theory, cut and dry, Leidholdt says. The formula goes like this: the FBI opens its own investigation, while the State Department works to provide consular assistance to family members. This is the case whether the citizen is born on American soil or not.

However, none of Sandra’s family, friends, nor coworkers have been contacted by anyone from the FBI to date, despite their many phone calls and emails to the intelligence agency, seeking its help. Neither has her family’s lawyer. Multiple attempts by WatersTechnology to reach the FBI’s criminal justice departments were also unsuccessful, and it’s unclear whether a case number has ever been assigned to Sandra Villena’s murder by the nation’s principal federal law enforcement agency.

“That’s the way the protocol should be followed. And if it isn’t, I would be concerned that there is a lesser standard of protection provided to this victim and a lesser degree of support to the family of this victim,” Leidholdt says. “Would this have happened if she had not been a naturalized American citizen, but someone who had been born in the United States?”

***

The only sister to three brothers, Sandra was an extrovert who loved to sing, dance, and compete. Growing up, she attended a Catholic school, and she spent her evenings enthusiastically poring over homework to the point of neglecting her toys (and chores), recalls her mother, Ada Manrique Borrego, speaking with WatersTechnology through Rosa.

When she was 12, Peru hosted a singing contest that saw more than 300 entrants. Seven were chosen to advance to the next round, including Sandra, who happened to be a couple years younger than the contest’s minimum age requirement. After fudging her age to compete in the first place, she could no longer hide her pre-teen status and was eliminated.

“You did this not because you wanted to be popular or famous,” her father, Gerardo Villena Calvo, told his disappointed daughter, “but to prove to yourself that you could do it.”

When she turned 18, Sandra traded Peru for New York, which was meant to be a temporary move. She decided to stay when she fell in love at 19 and got married, but the union lasted only a handful of years. Gerardo worried for his only daughter, alone in a new country and barely an adult, but reminded her of the reason she was there: to become a professional and to secure the best life possible for herself.

She received her degree in economics from Baruch and began her first financial role at Broadridge in 2016 as a product manager in the brokerage processing services division. She left in 2017 to join CJC as a market data engineer. It was there that she developed an affinity for engineering and had planned to pursue another degree in the discipline, but she never got the chance.

In her career and her professional relationships, Sandra was fearless and dependable, says Tom Tofte, head of managed services at CJC. But she wasn’t a drone—she was just as well known for her ability to dish out a great restaurant recommendation for any cuisine or travel suggestion for any destination in a moment.

Her presence was comforting, and her absence is surreal. “It’s an ineffable experience,” Tofte says.

They had said goodbye to each other on a Friday, which had carried the assurance of saying hello again on Monday. But by that afternoon, when Tofte still had not heard anything from Sandra, he felt that something was very wrong.

“If it was anybody else, you would say maybe something happened—maybe they lost their cell or something like that. But with Sandra, you knew that’s not a good sign,” he says.

***

According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, a US nonprofit and advocacy group, more than 10 million adults experience domestic violence annually. On a global scale, the World Health Organization estimates that 1 in 3 women have been subjected to either physical or sexual violence, either by partners or non-partners, in their lifetimes.

The statistics convey the gravity of an urgent human rights issue, but they don’t capture the very real, and sometimes inescapable, consequences of how abuse shapes its victims and those around them. Of the women introduced so far in this story, at least two of them have faced it.

When Julia and Sandra met in 2015, Julia, whose last name has been withheld, had been quietly trapped in her own abusive relationship. The pair initially forged a collegial relationship, and they worked well enough together to place as finalists in the Professional Risk Managers’ International Association’s Regional Case Study Competition that year.

For years, no one suspected anything was wrong with Julia, or if they did, they deemed it either impolite or unimportant to mention it. Then, a physical altercation with her former partner landed her in the hospital in 2018. She confided in the hospital’s social worker.

“I’m going to tell you right now, from my professional experience, if you don’t find a way to leave this situation, you’re going to die,” the social worker said to her. “Do you want to die?”

Before domestic abuse moved from an abstract concept to a bitter reality for Julia, she didn’t understand why or how women in these kinds of relationships stayed with their abusers. But as she learned, leaving is not just walking out the door, and it is not filing a police report. Leaving is concocting a strategy, sometimes with only one opportunity, that involves a network of trusted people, deception, money, shelter, grit, and, not least, the ability to plan and execute in the long term, while living in survival mode every day. Leaving means staying gone.

With the help of Safe Horizon, the largest victim services nonprofit in the US, Julia left. Sandra, whom Julia had come to know as considerate and fiercely empathetic, became her confidant, and the pair became close friends. For a time, they spent birthdays in the Hamptons, danced all night in the city until last calls, popped down to Miami, and generally lived their best lives.

It would have made a better ending.

***

It was in the front row of a Saturday class in econometrics at Baruch that Sandra met Carlos Martinez, a mild-mannered and bespectacled fellow South American, who had exchanged his home country of Colombia for New York and a job at State Street. She was impossible not to notice—seated in the front row with a tape recorder and a hand that couldn’t stay out of the air, she never missed a note and always asked a question.

She was so noticed that, at the end of one of the first classes, a huddle of classmates formed around her, asking whether she could share the recording with them. Carlos was almost too afraid to join the scrum, figuring she might be annoyed by yet another request to share her notes.

If it wasn’t too much trouble, and only if she didn’t mind, he meekly asked her the favor and gave his email address. She asked him if he spoke Spanish. He said he did. She told him she didn’t believe him. And they became the best of friends.

When they met, Carlos had been going through a rough patch with his mental health, which he didn’t talk about with anyone. But Sandra, who had come out of left field in his life, as Carlos tells it, could pry it out of him effortlessly. Over the best ramen bowls one can find in Koreatown, and between the meditation classes in Midtown that she had dragged Carlos to more than once, Sandra would always ask, “How are you doing? Like really?”

“She understood me. She picked me up from who I was and changed me,” he says.

They never lost track of each other, even after she moved back to Peru. For her last birthday—April 29, 2022—Carlos, Sandra, and a friend of Sandra’s from Peru, Yanin, flew out to Cartegena, Colombia to celebrate. She turned 32. The trio kept an ongoing group chat. At the time of Sandra’s death, they had been planning the next trip they would take. He remembers her excitement for it, right up until the end.

“Friendship transcends death,” Carlos says, through tears. “You become a good person when you’re right next to someone like her. I’ve been speaking with a lot of friends, and it’s always the same thing: I became a better person when I was with her.”

c1a3.jpg)

***

“If a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?” is a question with an unsatisfying answer, whether you approach it scientifically or philosophically. Sound, after all, is just vibration that must be perceived through the senses to be interpreted. The question is really whether the vibration, taken by itself, matters. If perception is all that counts, does a tree that’s never viewed by an eye exist? You can’t prove it does.

Perhaps the question has the wrong focus; perhaps it’s better to ask whether it has an impact. When a tree falls, does it leave splinters on the ground, roots in the earth, and a void in the air? It does. Sandra Villena can neither be seen nor heard in the same way you can look at a tree or hear a crash. But her existence and its evidence are everywhere.

Julia, who had been on track for a financial career, became a court advocate with CASA Union County, an advocacy group for children in the New Jersey child welfare system following Sandra’s death. Farah is supporting and donating to three organizations that serve victims of domestic violence—Pillars of Peace, FACE, and Asiyah Women’s Center—and she has recently secured a full-time role with a social impact status since leaving her role at JP Morgan Private Bank last year. And she continues to write and process her grief through micro poems, a hobby of hers that Sandra inspired, encouraged, and championed. Carlos is a different, and better, person.

The dog Sandra left behind, a shih-tzu named Rita, now resides with Sandra’s mother and keeps vigil at her side. Her father made the decision not to tell his mother, Sandra’s grandmother with whom she was extremely close, about her death due to her declining health. A gaping hole runs through the middle of their family.

Yet, some things remain the same, like the undereducated and under-resourced society that allows women like Sandra to fall through cracks that shouldn’t exist.

When Julia was in the process of leaving her former relationship, she consulted her workplace—her financial security would be in question during the transitional period, and she wanted to be able to count on her employer, a large US bank, for protection—where she says she was treated with contempt and left with the feeling that she was too much to handle.

“They treated me as a liability at that point,” she says. “They didn’t say so, but treated me as if they wanted me out of there and said some pretty terrible things to me.”

The exchange etched a stark contrast between the reality of reporting abuse at work and the corporate emails routinely sent around every Women’s History Month or Domestic Violence Awareness Day (October 20 in NYC).

***

Before Sandra, her family, and her friends were robbed of the future they’d all envisioned together, Farah had been preparing a photo book of wedding photos for Julia, which she never got to print. She had two stacks of 4x4 photos, one for Julia and one for Sandra, that she had been saving to share the next time the group all got together.

“In a pandemic, where nothing is certain, that friendship was certain. It felt certain that we’d have each other in our lives—that we’d have time,” Farah says.

Time, that most fickle of concepts, and that which, when it ends somewhere, forces you to ask whether it’s better to prepare for the worst and be pleasantly surprised or assume the best, or even the average, and be blindsided.

Time is the reason Farah never printed the book, and it’s the reason Sandra and Farah were just a bit late to the wedding.

For the first time, over Zoom, Farah’s voice cracks. “We thought we had time.”

Women at work

According to the last US census, taken in 2020, women account for nearly half the national workforce but hold only 27% of STEM roles. They had made gains, to be sure—8% of STEM workers were women in 1970—but progress had come at a glacial pace.

Sandra’s colleague at CJC, Tom Tofte, tells WatersTechnology that she had an interest in understanding how the company’s software operated technically, and how it interacts with the operating system and hardware.

“And she had a knack for it,” he says. He had recently begun giving her managerial duties, such as coordinating datacenter changes and maintenance plans—a task that boiled down to juggling several moving parts at once, and which is a skill not everyone has.

%20hzd637.jpg)

“She did seem to like the engineering side—the nuts and bolts and the fiddly bits and how they all worked together,” he says. “And she would have progressed toward that with a couple more years’ experience in a natural fashion.”

Wei Zheng is the associate professor of management and Richard R. Roscitt chair in Leadership at Stevens Institute in Technology, a private university in New Jersey. Her research specialty sits at the intersection of leadership, diversity, and inclusion.

Though she sees in her work, and at her own college, that the number of women seeking higher tech education is growing, there remains a host of workplace challenges for women—things researchers call “male defaults”.

The traditional workplace—whether in an office, remote, or hybrid—is set up to be more friendly to men than women, Zheng says. For instance, it’s not uncommon to hold work meetings or schedule calls as early as 7 a.m. or as late as 9 p.m., particularly when workers’ time zones conflict. But often, work obligations such as these are particularly difficult for mothers with young children to navigate.

“And it’s a lot of other things. For example, how do you celebrate? Where do you go for company outings?” Zheng says. “It’s been changing, but these are invisible things that people take for granted.”

And while more female representation and thoughtful accommodation have become mainstream workplace issues—particularly with the advent of socially responsible investing—there remains a taboo that most employers still don’t want to touch: domestic violence.

Julia’s story is a common one. For a past review article, Zheng compiled all the empirical research that studied the effectiveness of gender equality practices in the workplace. Despite the large number of women that will experience domestic violence in their lifetimes, she found very few employer-led support programs for victims. The lone exception she found was cosmetics companies such as Avon and L’Oreal.

“It’s something that should be talked about more. It’s like menopause, right? Female issue—don’t talk to me about it in our workplace. But it’s so real,” Zheng says of the natural hormonal stage that affects middle-aged women. “It has to do with productivity, profit, effectiveness, performance, and all sorts of relevant workplace issues.”

“And I wonder whether domestic violence is such a female issue that it’s less likely to be included. But it’s so crucial because those are the people who need the most help.”

For women stuck in violent home environments, the place they spend 40 hours or more per week could be and should be a refuge. But it often isn’t.

Story by Rebecca Natale

Photo illustration by Siemond Chan

Spanish translation by Carlos Reyes and Natacha Maurin

Special thanks to Rosa Loza for her help coordinating several interviews with Sandra’s family and friends across time zones and language barriers.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@waterstechnology.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.waterstechnology.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

More on Comment

In Absentia: Recordando a Sandra Villena y en búsqueda de su Asesino

Sandra Villena, una profesional de datos de mercado de 32 años con gran promesa, fue asesinada mientras estaba de vacaciones en octubre de 2022. Casi un año después, sus amigos y familiares todavía buscan justicia, mientras aprenden a vivir con la ausencia que ahora llena sus vidas.

Demystifying private markets liquidity in 2023

Private markets are being democratized at an alarming rate, and the new entrants’ structures could be misleading. Time to cut through the noise.

Understanding investor overlap across late-stage private stocks

Investing in private markets is no longer just for venture capitalists and private equity funds. But as demand for stakes in these companies grows, so does the overlap in who is investing, as well as calls for more consistent valuations.

People Moves: DTCC, Octaura, Baton Systems, and more

A look at some recent people moves in the capital markets tech and data space.

American unicorns: When primary rounds are distant, secondary markets provide clarity

Unlike in the public markets, valuations of so-called ‘unicorn’ start-ups might only be updated following funding rounds. What if investors want insights more frequently?

Beware the duty of care! Why a level playing field for responsible data sharing in financial services is essential

By Elise Soucie, associate director, technology and operations division, at the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (Afme)

The tortoise and the hare ... and the unicorn

Where will private market unicorns finish in the race between the public market tortoises and hares? ApeVue looks at data from the opaque private markets for answers.

Waters Wrap: On getting back to normalcy

As “work from home” becomes the new normal, Anthony explores his own anxieties and whether they mirror similar trends unfolding in the workplace.