Confidential computing won’t save you from data breaches—but it can help

A Google exec and a Stevens Institute director lay out the potential and the pitfalls of this emerging cloud computing technology for data protection.

Data privacy and security is a minefield. A cybersecurity team can deploy layers of encryption, firewalls, and anti-malware to protect their organization, but a savvy hacker needs only one loosely defended entry point to wreak havoc.

With well-organized hacking groups able to take servers offline for days or even weeks—as seen at the end of January, when LockBit forced Ion Trading to shut down a key futures trading service using ransomware—privacy-enhancing technologies have been touted as a safeguard against data leakage and theft. The young technologies in this field sound like they could be plot devices in “The Matrix”—homomorphic encryption, zero-trust architectures, and confidential computing, for example, have enticing names and convincing propositions but a fair number of holes.

Data exists in three states: data at rest (databases and archives), data in transit (email sending and file downloads), and data in use (payment processing, document creation, or computations, among other uses). More traditional types of encryption have mostly solved for protecting data at rest and data in transit, but data in use has been data security’s Achilles heel.

Confidential computing aims to protect data when it’s in use. A piece of hardware called a trusted execution environment (TEE)—which is a physical chip—encrypts data stored on the TEE on a pervasive basis, meaning that even if there were some breach and the data were made public, it would remain unknowable to everyone except the user who holds the encryption key. It cannot even be known to the underlying cloud provider.

Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, and Amazon Web Services have each launched competing confidential computing services over the last couple of years. A bank consortium called Danie, led by Societe Generale, is seeking to use this technology, supplied by confidential computing specialist vendor Secretarium, to reconcile its members’ encrypted and anonymized Legal Entity Identifier (LEI) records to ensure their records are up to date without giving away sensitive information such as client data or relationships, and without having to pay an intermediary.

And in August 2019, household tech names such as Microsoft, Google, IBM, Intel, Facebook, Alibaba, and others banded together to form the Confidential Computing Consortium.

The need for such services—as well as for them to be scalable, usable, and, of course, high-performance—is best underscored by the ever-widening talent gap between available cybersecurity experts and cyber criminals, says Nelly Porter, head of product for Google Cloud’s confidential computing and encryption business.

“We cannot talk our customers into using this technology unless they can take their line-of-business applications [and] analytical prediction apps and move them without any line of change—literally none—to a confidential environment,” Porter says.

Google’s offering utilizes a chip made by chip manufacturer AMD that runs on the Caliptra project, a newly developed open-source specification for chips developed in partnership by Google, Nvidia, AMD, and Microsoft, and maintained by the Open Compute Project and the Linux Foundation. Porter says that using the AMD/Caliptra chip was an intentional choice not to use Intel’s SGX chip—the TEE that powers many of the existing confidential computing environments running today—due to SGX’s memory limit of 128 megabytes.

Late last year, Google also created an additional service as part of its confidential computing portfolio, called Confidential Space, which is intended to enable cross-organizational collaboration on common pain points without exposing sensitive data to competitors. The aim is very similar to that of Danie and Secretarium’s Semaphore app: to provide a way for banks—which all maintain reference data at considerable cost and to no competitive advantage—to conduct non-differentiating tasks, such as know-your-customer (KYC) checks, with each other’s help.

Tools like Confidential Space and Semaphore would allow banks to cross-check their data with one another. Does company X have a politically exposed person (PEP) on its board, for instance? Or does the LEI that one bank associates with company Y match the one that another bank has on record? If one bank notices it has not recorded a PEP associated with a particular company, for instance, that becomes the impetus to check that its records are up to date.

“The whole world has silos by design. But confidential computing helps to break them, to help people collaborate securely across those boundaries. Those silos are created based on government boundaries, regulation boundaries, privacy boundaries, even within the same companies. However, the question is how to ensure that they can communicate properly and on their own terms without exposing private data that certain people should not look at,” Porter says. “We couldn’t solve this problem without confidential computing.”

Good for today

Despite the hype—and the funding—critics of confidential computing name cost as a barrier to adoption. Though it’s a cloud service, the necessary TEE hardware component adds both money and complexity. And given that the data inside a TEE is meant to be isolated, secure, and inaccessible to unauthorized parties, an organization employing confidential computing would need to have multiple separate and dedicated TEEs for disparate use cases.

“It is not a panacea,” says Michael Frank, teaching associate professor and director of the master’s program in information systems at the New Jersey-based Stevens Institute of Technology. “I think it’s very noteworthy, but it doesn’t solve some of the major problems in the banking industry.”

Frank has a storied history in cybersecurity. He has served as chief information officer for Emigrant Bank and chief information security officer for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. He was also an expert witness in the Federal Trade Commission vs. Wyndham Worldwide Corp., the global hotel chain—one of the most significant cybersecurity cases in history next to the Target breach in 2013.

In both cases, Frank explains that the breaches happened downstream. An HVAC vendor enabled hackers access to Target customer data, while hackers accessed a Wyndham franchisee before stealing customers’ credit card data from a central company server. Wyndham would be hacked three times in total between 2008 and 2010 before the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) brought charges against the hotel company.

The court found that Wyndham failed to maintain reasonable and appropriate data security practices for sensitive customer data, and that—even though a franchisee, not the parent corporation, was the target of the attack—the parent company still shouldered the blame.

Frank is not so much a critic of the technology; rather, he’s more of a cautious observer. At Stevens, he teaches a class in emerging technologies and digital innovation. He believes in moving forward. He also believes that cybersecurity is more of a business strategy and protocol and less of a breeding ground for a technological nirvana.

“The assumption on confidential computing is the chip is perfect. It is not. It’s a piece of program that happens to be in silicon,” Frank says. “Ultimately, anything you hear about confidential computing is only good to the day it was given to you. Tomorrow, there’s going to be some other physical issue with those chips.”

Further reading

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@waterstechnology.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.waterstechnology.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

More on Emerging Technologies

Quants look to language models to predict market impact

Oxford-Man Institute says LLM-type engine that ‘reads’ order-book messages could help improve execution

The IMD Wrap: Talkin’ ’bout my generation

As a Gen-Xer, Max tells GenAI to get off his lawn—after it's mowed it, watered it and trimmed the shrubs so he can sit back and enjoy it.

This Week: Delta Capita/SSimple, BNY Mellon, DTCC, Broadridge, and more

A summary of the latest financial technology news.

Waters Wavelength Podcast: The issue with corporate actions

Yogita Mehta from SIX joins to discuss the biggest challenges firms face when dealing with corporate actions.

JP Morgan pulls plug on deep learning model for FX algos

The bank has turned to less complex models that are easier to explain to clients.

LSEG-Microsoft products on track for 2024 release

The exchange’s to-do list includes embedding its data, analytics, and workflows in the Microsoft Teams and productivity suite.

Data catalog competition heats up as spending cools

Data catalogs represent a big step toward a shopping experience in the style of Amazon.com or iTunes for market data management and procurement. Here, we take a look at the key players in this space, old and new.

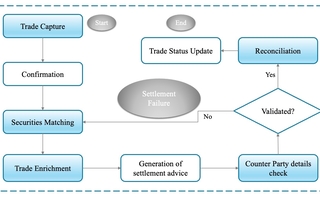

Harnessing generative AI to address security settlement challenges

A new paper from IBM researchers explores settlement challenges and looks at how generative AI can, among other things, identify the underlying cause of an issue and rectify the errors.